Prologue

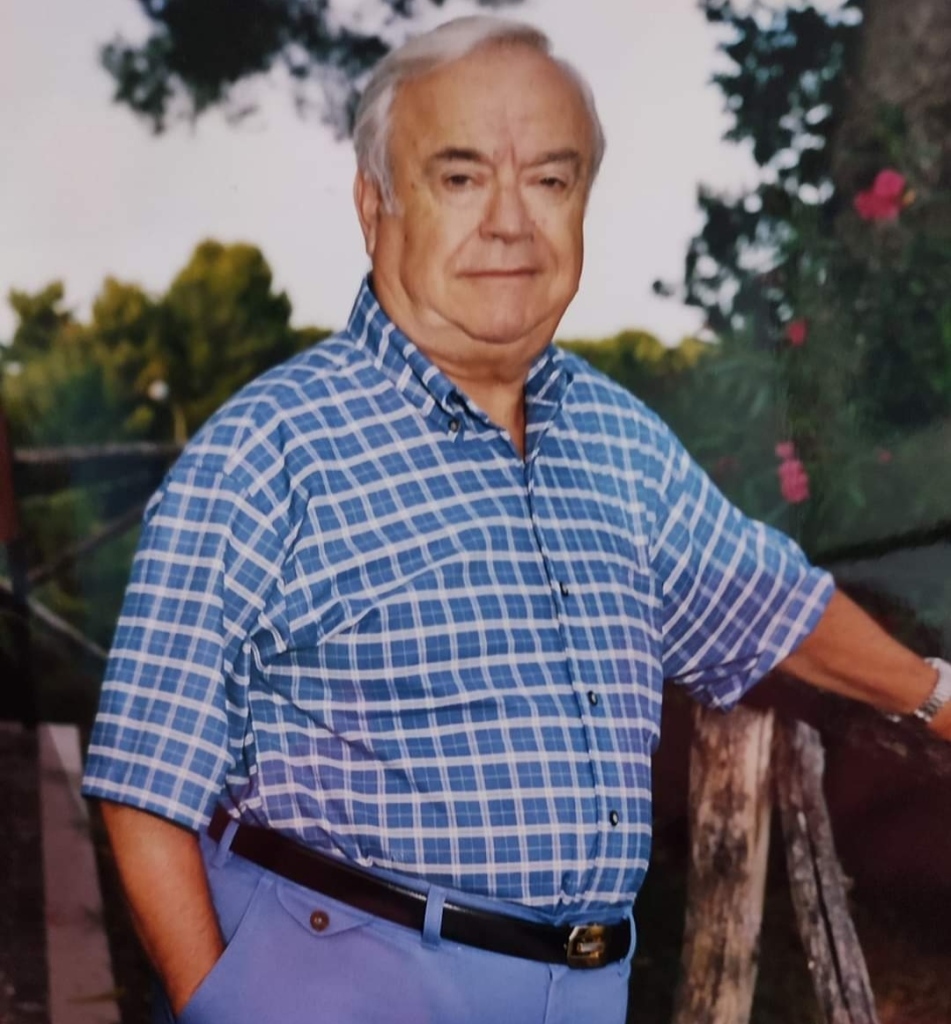

I’ve been trying to write this piece for over a year and a half. It’s not easy to put into words the feelings I have for my father. To pay tribute to him is a complex task, because he was a complicated man. On the one hand, he was dynamic, affable, inspiring, and on the other, he could at times be stubbornly uncompromising, especially in his later years. When I would complain about this and try to get him to see another point of view, he would say, “Pia, I am a man of convictions”. I often chalked up his lack of “diplomacy” to the fact that he was brought up by his mother, who apparently was of similar character, and who raised him alone for over 14 years.

Single parenthood in 1930s Italy was perhaps even more complex than today. A mitigating factor might potentially have been the presence of his father or the influence of the extended family as he was growing up, but in his case, the extended family environment on his father’s side was hostile, while his dad lived thousands of miles away. This, the war, and his other early hardships seemed to have left him with a hunger to reclaim what he had lost, that served as a catalyst for his personal ambitions. In other words, hardship didn’t leave him crying over himself, it instead seemed to boost his confidence, but in some way, it changed his sensitivity. This may have been a survival tactic that served to bolster a frightened boy who probably felt overwhelmed by life at certain times.

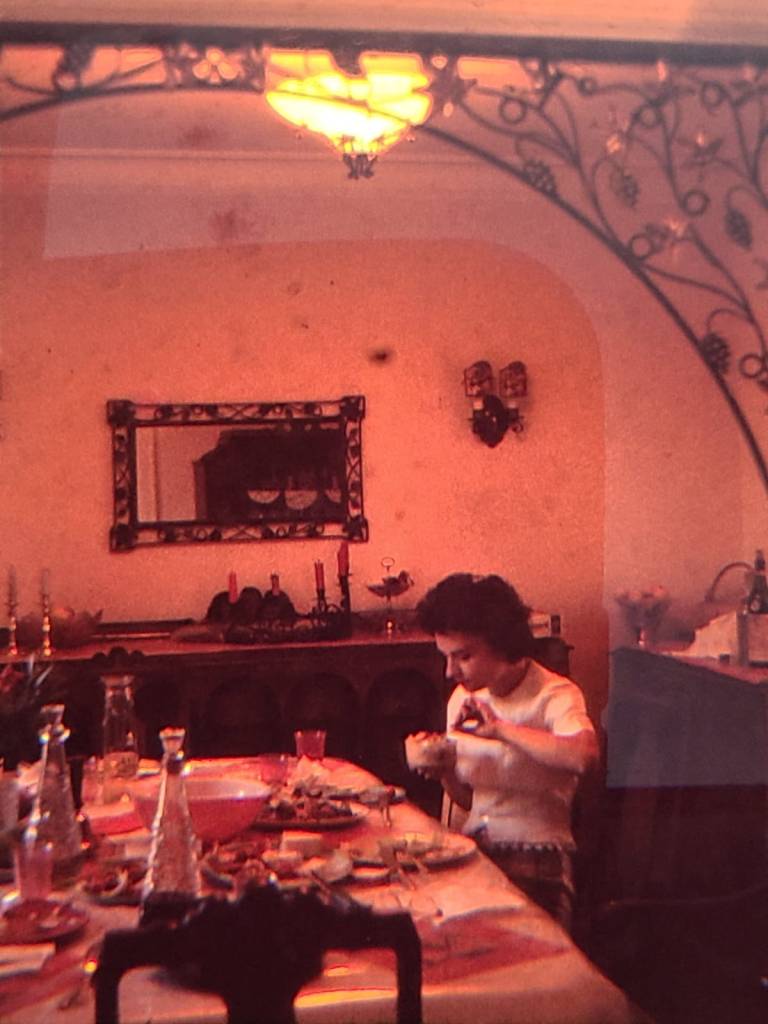

As a young father, he tried to instill in us the solid values he’d grown up with, especially in terms of faith. He would stand in the hallway between the boys’ and girls’ bedrooms and we would say our prayers together every night. I still remember that when I was little, he used to give us our baths at night. He would put me in the washing tub in the laundry room, because it was more comfortable for him than the bathtub. Then he would wrap me in a big towel on top of the washing machine, and call me “Big chief Nincompoop”.

Music was another element at the basis of our family. And not just any music. Italian Opera was his passion and he exposed us to it from when we were tiny babes. We often went to concerts and operas at the Academy of Music and The Met, something that most other children did not do.

His other passion was all things Italian. His understanding and pride in Italian culture constituted his very Essence as a human being. He managed to mesh it in and make connections to it even in his American Literature classes. He instilled this deep love in each of his children.

It’s hard to accept when our parents start showing signs of aging. In his last few years, the aspect that stood out more than anything else was his loneliness, something that seemed as foreign to me as if he’d suddenly started going to discos. He would complain to me that he was lonely, but in reality, he seemed to want to be “with people” only on his own terms.

Amazingly, he learned to cook at age 80 after my mother died, and every weekend he gave my sister Rosanne a lot of cleaning up to do, at the expense of quality time. After a couple of incidents when he almost burned down his place, he finally accepted that someone else would have to prepare his meals. Even so, he ate very sparingly, and had cravings only for foods that reminded him of his childhood: pizza e foje (broccoli rabe with corn meal “pizza”) or baccalà, or some other complicated, out of season or impossible-to-get food. Then, when my brother, Francis would make it for him, he wouldn’t even eat it. Like many seniors, he seemed to be lost in the past, maybe because the present was too hard to accept. I wouldn’t call it dementia, though. His capacity to reason was as sharp as ever. About a year before he died, we were talking about some situation that sparked a lesson about the literary tool of irony. Needless to say, that conversation left me in awe and made me smile. But, still, it’s hard to accept the changes that age brings with it.

A few years ago, I read “Go, Set a Watchman” by Harper Lee just after it came out. I was looking forward to reading this new work by this great writer who was, and remains one of my favorites. “To Kill a Mockingbird”, and the relationship between Scout and Atticus Finch mirrored my feelings toward my dad and thus had a huge influence on my youth and early adulthood. Of course, having read Harper Lee’s masterpiece for my dad’s English class played a role in this connection. It seems that in much the same way, “ Go Set a Watchman” has left its mark on my older years; the adult protagonist casts away her rose-tinted glasses and is forced to look at her father under a more realistic light. I guess it’s something that comes with age.

In “Go Set a Watchman”, Scout’s realization that Atticus is not perfect causes a shift in her. However, it is a shift that she is able to recover from, because she realizes that, no matter what, he is still at the foundation of her sense of identity. Harper Lee sums it up like this: “She did not stand alone, but what stood behind her, the most potent moral force in her life, was the love of her father. She never questioned it, never thought about it, never even realized that before she made any decision of importance, the reflex, ‘What would Atticus do?’ passed through her unconscious; she never realized what made her dig in her feet and stand firm whenever she did was her father; that whatever decent and of good report in her character was put there by her father; she did not know that she worshiped him.”

*****************************

WALKING IN STEP

When my dad was young, he used to walk to a different beat. I mean really; whenever he went anywhere on foot, he’d snap his fingers rhythmically, at times humming a tune, and fall into step naturally and decisively, as if he had places to go and things to do, which he did of course. And he was fast. Whenever we went anywhere with him, we’d be scurrying like ducklings trying to keep up with their mama. Except our mama always brought up the rear, and she’d complain that he needed to slow down. I believe that rhythmic, purposeful walk is the perfect metaphor for his life.

As Francis always says, it was as if he was driven; no matter what endeavor he undertook, and he continuously undertook endeavors, he was motivated by an unquenchable desire to learn, to be involved, to leave his mark. Otherwise, how could he possibly have worked 2 full time jobs for over 40 years? During his lifetime he had been a teacher, a lab technician at Merck, a cashier ringing up groceries at the Acme and Pantry Pride, a tour guide to Italy, an opera afficionado, a champion fighting for issues he felt strongly about. He did many of these things in the same time frame, while also earning three degrees. He couldn’t do anything practical as a “handyman”, but he had been a radio show host, an impromptu driving instructor for immigrant students, a tutor, a translator, and a writer, most especially of scathing letters denouncing pet peeves to the editor and readership of the Norristown Times Herald, and of course, of his book, “Suffer the Children: Growing up in Italy during World War II”. These were the things that I was certain about my father. But there is so much I didn’t know. Recently I’ve been given a fresh, surprising look into what his life as a teenaged immigrant to the US was like, from a packet of old letters that were sent to me by my brother after dad died. This is the most precious gift I have inherited from him. These letters have allowed me to become the proverbial fly on the wall, not only of his past, but my grandmother’s as well, because there are several letters that she’d written to her husband, detailing her trials and tribulations over the years.

With all of this material, plus the stories from my other, most important reference work, my dad’s book, I’ve been able to piece together my theory, that the source of my father’s drive was for the most part attributable to the influence of his mother, Maria Sorgini. Through thick and thin, she did her utmost to help him and his brother Philip not only survive the war, but thrive in its aftermath so they could have a chance at life. Therefore, to understand the man, I have had to take a step back to understand the woman who gave him life.

The most important goal for my grandmother was that her children had to get a well-rounded education. She wanted them to rise above the ignorance that surrounded them, principally in their own home, where they were quite often at the mercy of their petty, mean paternal grandparents. From her letters I learned how they systematically denied her and her children even the most basic of needs: a handful of flour to make pasta with or a safe haven in their country cottage when the first bombs started raining down on the town center, where they were living at the time. They had moved away from the DeSimone clan’s home a couple of years before, after the daily bickering with her father in law had distressed her one time too many.

The patriarchy that reigned in southern Italy had an unwritten set of rigid rules. The father figure was the dispenser of justice, discipline, and even basic necessities like food and clothing or a bed to sleep in. As a daughter in law in the absence of her husband, my grandmother had no rights. When she could no longer bear this situation, shortly before the war, she had taken courage and left with her two boys, returning to her family home in the center of town. That home was roomy and comfortable, and it was there that she set up shop as a seamstress and embroiderer. She was very skilled in both areas, very popular among the ladies in town. The house had been built by her father, Filippo Sorgini, with money earned in the United States. Nonno Filippo was in the States when the war broke out, and his plan to retire in Italy was thwarted by these circumstances. My paternal great grandmother, Concetta Sisti, was the rock that my grandmother, my dad, and my uncle counted on through those years and afterwards.

Nonna Maria was a very smart, independent-minded woman who had engaged an epic, unflinching battle with the patriarchal mentality of the time, which is just the way it was in most families back then. Alone, except for the steadfast help of her mother Concetta, she survived the war that had forced her and her loved ones to be marched through muddy, rubble-strewn villages and minefields in search of a safe haven, only to return to the complete annihilation of the town, and worst of all, the family home. From that moment, these women and children struggled with homelessness and strife until their application to join my grandfather in America was approved.

My paternal grandfather, Nicola De Simone, had emigrated to the US in 1920 with his father, who had first emigrated from Italy in 1898. Through their hard work, they had saved enough money to buy some choice property in the countryside below the hillside village of Fossacesia. In 1926, after one of his visits to his family, my great grandfather decided to stay, wishing to settle in and enjoy his property with his wife, two daughters, two daughters in law, and several grandchildren. After she and Nonno Nicola were married, my Nonna Maria accepted to live with her in-laws until my grandfather, who had returned to the US, could send for her.

During that time, Nonna Maria was often forced to remind her father in law how much his son had contributed to the well-being of the family. However, over the years, whenever she needed to ask her father in law for “her husband’s part of the harvest earnings” to buy new clothes and shoes for the children, the answer was always a sonorous no. She offered to work on the farm in his place to earn her part, but to no avail. The answer was always “When my son returns, I will give him his part of the earnings,” and “you can’t do this kind of work, you’re not used to it”. This had been going on since the moment her husband returned to the US, and after his subsequent two trips back home, the “fruits” of which were my father and his brother Philip.

Before the war started, the money sent through a wire service by my grandfather, my grandmother’s primary source of relative independence, together with her dress maker income, was sufficient, but when this service was suspended, Nonna Maria had to increasingly turn to her father in law for practically everything. Then, just after the allied front had liberated the area, she witnessed the demolition of her beloved home, that had seemed to miraculously escape damage, but it had tragically been marked by the British corps of engineers as uninhabitable, because two craters on the streets in front of and behind it had weakened its structure. It was blown up, together with all of Nonna Maria and Nonna Concetta’s linens and porcelain, as well as my dad and his brother Phil’s books.

Having nowhere to live, she begged her father in law to let them stay in her bedroom in the main residence of the DeSimone family in town. This building had come away with only slight damage, and the bedroom in question was the one she had shared with her husband when they were married and on his rare trips to Italy. He had set it up with beautiful furniture, and it was in that small, private space that their two sons had been conceived and were born. Nevertheless, that room was deemed by her father in law to be off limits when her husband wasn’t in Italy. It had to be preserved for the next time he came, an event which never happened. My grandfather hadn’t managed up to that point to get his family to the States, either, as he’d promised many times over the previous 15 years. So, the answer was no. Period. Never mind that my grandmother had practically saved the whole family during their displacement, with her sharp wits and common sense. She had guided the family’s defensive tactics when moving from one area to another for weeks while the front raged through.

At this point, having no other choice, Nonna Maria took her mother and sons to a cousin’s place for a few days until a friend offered her and abandoned shed that had formerly housed chickens and maybe the odd pig in peacetime. They cleaned it up, brought an extension of the power line to it so they could at least have light at night for the boys to study under, and moved in a short time later. They lived in this shack for a couple of years, without heat or running water (actually, no one had running water at that time).

A couple of years after the war, in June 1947, my dad, my uncle Phil, their mom, and grandmother finally left Italy with high hopes in a brighter future after years of torment. Tragically, their optimism was crushed just a year later, when Nonna Maria died, shortly after giving birth to my uncle Frank. The wounds caused by this devastating event had profound effects on everyone, but most especially on the young boys and the infant that had just come into the world. In the wake of this tragedy, great Grandma Concetta reached even greater heights of dedication and service to the family by helping to raise little Francesco until the day she died a while later.

Until then, my father seemed to have acclimatized himself well to life in the States. His letters tell me the story of a young boy who had an innate ability to adapt to his new circumstances, learn the language, and make friends. With the example those dynamic women had given to follow, my dad did his best to go on, despite the heartbreaking series of misfortunes he’d suffered. My father’s letters after his immigration are extremely interesting to read. His way of expressing himself is like a snapshot of the man I remember so well, the young Danny. After devouring these letters, I can sum things up by saying that throughout this life, my father always remained true to himself. His personality was very well forged even as a teen. Besides being a staunch, unwavering Catholic, (in my eyes, at times to a fault), he believed in his education just as much as his mother did. But he didn’t do it as an obligation: he truly enjoyed learning. He was brilliant and inquisitive. He studied hard and had no trouble adjusting to the American education system, so very different, and much easier to navigate than his classical studies in Italy. He effortlessly adapted to the American social life, enjoying roller skating, going to the shore, or to the movies. He embraced a rich social and cultural lifestyle by taking advantage of every opportunity America gave him.

Some of his other letters tell me about a kid who missed his friends and the life he led in Italy. He would tell them about his latest adventures and then ask them about the latest gossip, meaning “who liked whom?”.

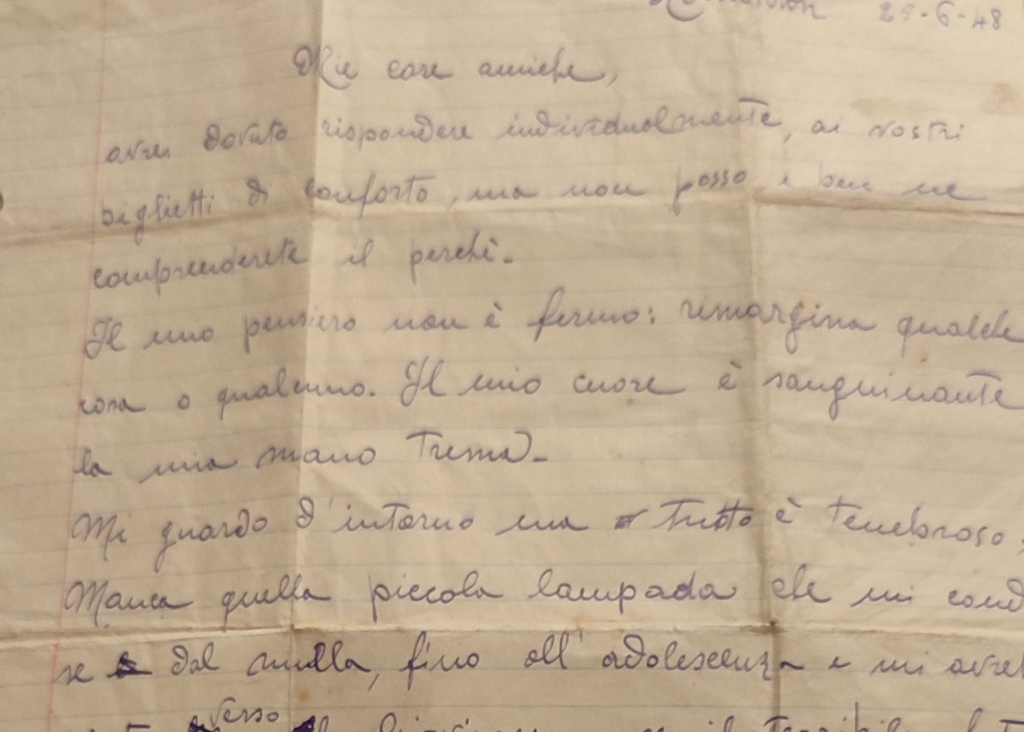

The most revealing letter in the packet was the first one he sent to my mother and her sister three weeks after his mom died. “My thoughts are not firm”, he wrote. “They keep searching for something or someone. My heart is bleeding, my hand is shaking. I look around, but everything is dark. I’m missing that little light that led me out of nowhere to my adolescence, (the light) that would have propelled me towards my young adulthood, if fate hadn’t put an end to her boundless love…here I’m asking you for a word of comfort. Yes, I’m really asking you, because I know that only you can give it to me. You, who are my only friends…I also include a greeting, the very first, from little Franceschino”. There are no words to express the feelings this letter has awakened in me. I can’t help but think what an amazing man he was, to have gone through the war, displacement, homelessness, and finally immigration…and exactly a year later, to lose his mother.

Luckily, within a few years, things started taking a turn for the better. After graduation, he started working, and he finally went back to Italy to marry my mom. Then, as our family grew, he went to college, worked long and hard, and started teaching, which is where his vocation reached its full potential. I feel so fortunate and grateful that I had him in school. I recently went through my high school yearbook and had to laugh at what he wrote in it. “It’s been a pleasure to have you in class, Pia. Now that it’s over, take heed from your old man and never be afraid to take that initial bold step. It’s the one that leads to great things. Love, Dad”. And he signed it with our motto “PS, You’re funny”.

I did take heed, and my bold step took me very far away. My step isn’t as quick or rhythmic as his was, but I have found my own pace. But it has come at a steep price. Very simply put, the price of missing my family, with everything that entails. I don’t think he meant for me to make that bold of a move, to go back to the old country. The example of my mother and father, indirectly my grandmother and grandfather De Simone and my grandfather Fantini, as well as all my other forebears who crossed the Atlantic in waves, coming and going between these two great nations in search of a better life, are a sterling example of the resilience and steadfastness that have been instilled in me.